-

Really good, clear visual guide to flexbox.

Five things I’m thinking about: July 2015 edition

29 July 2015

Not written here for a while. That’s not deliberate; just been busy, keeping up with work, keeping up with life. Lots ticking away in my head, for sure. So, as a way back into keeping the ball in the air, I thought I’d take another pass at five things that are currently in my head (five years ago, that list looked like this).

Non-traditional (and irregular) ways of composing music

I’m working with Richard on building a music box. You know: holes in paper, a handle you crank, tines being struck. Although ours is electronic: there’s no paper, and no tines; you punch holes in virtual paper with your finger, and can easily remove them if you don’t like them. The handle’s very much real, though, and that leads to all manner of analogue compromises – lumpy rhythms, the ability to play melodies backwards, and so forth. I write about this in my Weeknotes from time to time.

It’s an interesting way of coming up with music, though: sometimes, it’s cranking the handle at the right speed – or right selection of speeds – that makes the music happen. Sometimes, it’s the notes you choose. Sometimes, you don’t even choose them: it’s just a picture you paint with your fingers. It’s an interesting UI for composition, and it leads to all manner of interesting irregularities.

It also can talk to other MIDI devices. As of the latest stable release, Chrome supports WebMIDI, which means it can talk to MIDI ports from inside the browser, just using Javascript. And that means our music box can control anything with a MIDI input, from a software synthesizer, to external hardware. And that’s exciting: the idea that the browser is a platform for experimenting with note-generation.

That leads to interesting sound experiments, but also things that aren’t musical: I’ve long been fascinated with the idea of using grids like the Launchpad as a UI, and now that’s all doable inside my browser. I keep wondering what a render() method within Backbone for a Launchpad would look like.

(I’ve also been thinking about this having seen my friend James’ work on a sequencer for modular synthesizers, and the way unusual UIs force you into different compositional habits. There’s so much beyond timelines and steps to explore!)

The music box – Twinklr – has inspired the next item on the list, too.

Making PCBs

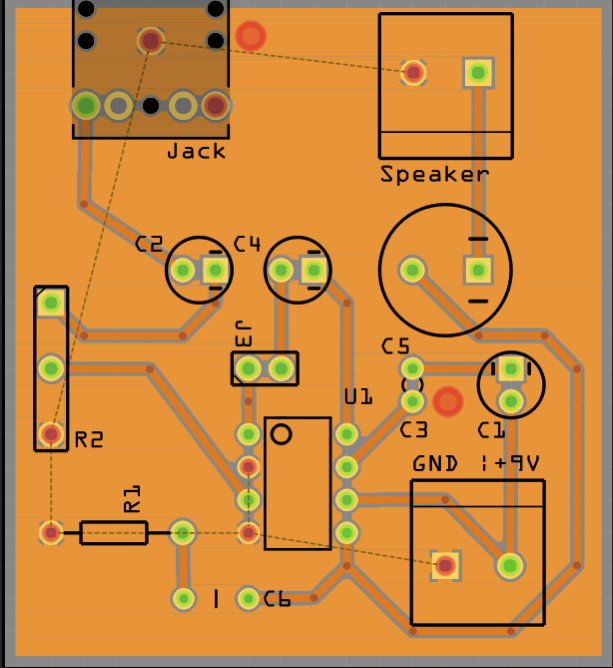

I’m spending a while at the moment thinking about making PCBs.

I’m really bored of the slightly amateur stripboard I tend to make circuits from, so am hoping to manufacture the PCBs inside Twinklr myself. That means learning how to route PCBs from schematics or ideas in my head, for starters. I’m using Fritzing of all things – EAGLE makes me feel stupid – but am making progress on some PCBs that are getting passable elegant. I even have a ground fill:

Of course, the next thing is manufacturing them, and I have all manner of tabs open with different recommendations on chemicals, techniques, and so forth. But it’s moving forward slowly, and I’m hoping that there won’t be any more unpleasant stripboards in future. Initial prototypes are suggesting that my homebrew PCBs might not be a go-er, and I might want to move to letting professionals manufacture them. But for now, I’m going to feel the materials with my own hands, and try not to get Ferric Chloride on anything.

Writing music

I’m slowly, carefully, returning to writing music again. I’ve produced music – largely electronic – since my late teens. Back then, it was on a variety of esoteric hardware. Now, it’s mainly inside computers, but with a growing tangle of instruments outside it.

I find this really hard.

What I find is: I will disappear into textures and sound design and harmonies and rhythms for hours on end, possibly just exploring the possibilities of a single sound… and by the time I ‘come up for air’, I hate everything I’ve done. Finding a way to compose with constant forward momentum, not looking back, not comparing myself to anything else I’ve heard… is so challenging.

It’s also rewarding: when I come back to something a day later and even if it’s not the best thing in the world, it’s a thing I’m happy to spend time with, a thing I have new ideas with. I hate the creative rollercoaster, and what I’m finally finding a way to do is to cling on and not let go. I still don’t like it, but I’d stopped riding it because I was afraid. And now I’m not. I’m working on finding ways to not repeat myself, not to fall into the same shaped holes, the same patterns and riffs. Which is also hard. But I’m turning up, at least.

I don’t mention the output, much. The Internet made our past-times and interests performative: sharing and showing-off are easy to confuse, and sometimes, I’m making sounds and music for myself. I’m so used to sharing things to all manner of services but, for the time being, it’s mainly just staying on my hard disk. It’s giving me pleasure; it’s time well spent. One day, I might share it.

Streaming, and its relationship to craft

I watch a surprising amount of Twitch: a service through which people stream themselves playing games. They’re not just sharing a screen; high-end streamers have chromakey rigs to insert themselves into the image, and manage large communities of people… who watch them playing videogames. It’s usually not nearly as interesting as it has the potential to be – although it’s great to tune into Evo live.

I know I said hobbies weren’t performative, but I’m fascinated by streaming things that aren’t games; streaming crafting, perhaps. (I greatly enjoyed BBC Four’s Handmande strand, three half-hour films of craftspeople at work as part of Four Goes Slow)

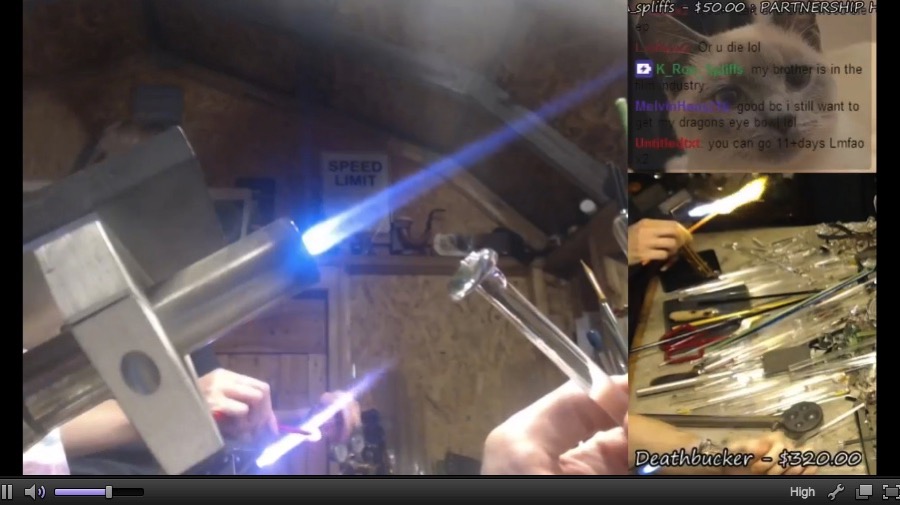

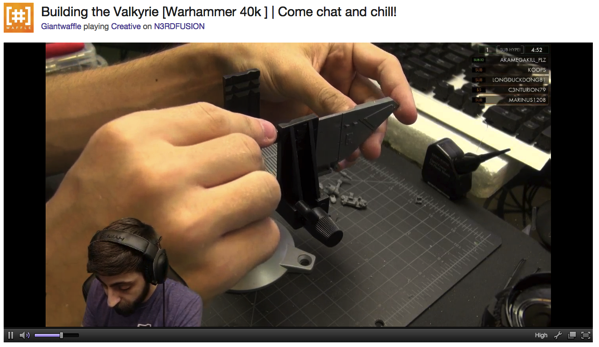

This chap does glassblowing on Twitch. I’ve watched a few people produce or compose music on camera. I watched a Counterstrike streamer get a hugely enthusiastic channel chatting whilst they watched him chilling out, putting together plastic model kits, one camera on his hands, the other as usual on his face:

It works surprisingly well. Obviously, it’s very time-consuming for large projects, but consider how sharing works in analogue craft: the tradition of ‘stitch and bitch‘ is as much about injecting a social element into a potentially solitary craft as it is about sharing with others. Recently, I have often wondered what Stitch On Twitch would look like. Not watching someone make a whole quilt: an hour of tuning in to chat to them whilst you craft too.

Slightly unformed, but it’s floating around my head. Streaming isn’t particularly great, but I think it’s suited to things people aren’t broadcasting on it yet.

Windows of time: schedules rather than moments

I really like the Spotify Weekly Discover Playlist. I like it because, so far, it’s been really good at recommending things to me. But I also like it because it’s weekly. It’s not updated every time I go to it; I have time for those selections to bed in, to listen to it like a mixtape. And because it comes around once a week, it then generates anticipation – looking forward to my new mixtape from the Spotify machinery. It’s not manufactured scarcity; it’s not the fiddly, artificial limitations of so many dual-currency free to play games; it’s just schedule. It’s a fixed window of time, rather than a right-now moment.

I still regularly play Destiny (Bungie’s MMO-FPS hybrid) and one of its strong points is its weekly calendar. (Apologies for the brace of jargon incoming – I’ll do my best to explain). Every week, the universe resets: a new Strike (like a Dungeon in World of Warcraft) gets picked to be the ultra-challenging “Nightfall”; a new Strike is slotted into the weekly ‘heroic’ strike slot, for players not up to a Nightfall; new playmodes are rotated into PVP; sometimes, a new temporary event runs for the week. On a Friday, the Trials of Osiris – hardcore endgame PVP for the very few – start, and run over the weekend. On Friday morning, the mysterious vendor Xûr turns up for 48 hours, and everybody sighs as he doesn’t have the three things they want. And if you don’t finish it all by Monday night – well, it’ll reset at 10am GMT Tuesday anyway.

Sometimes, the schedule enforces scarcity – trying to finish the Iron Banner event before the week is out; sometimes, it enables planning – getting friends together to run a Nightfall at the beginning of the week, so as to benefit from the XP boost. Sometimes, it’s just a reason to check back in to the universe. And if there’s nothing that week to do for you – well, you don’t need to turn up. Maybe swing by in the future. It gives the game a long tail to players who enjoy it, without forcing them to check in to “top up”, like so many Free To Play games.

I like schedules because they’re actually surprisingly easy to fit into life: if they don’t fit into your schedule this week, it doesn’t matter, because it’ll all start again next week anyhow – you’ll get a new playlist; you’ll get a chance to run a different Nightfall. But at the same time: it’s not constant newness, all the time; the weekly schedule gives you a chance to stick your finger in the page for a period of time.

I am not sure what this will get applied to in my own practice, but it’s a thing at the back of my mind.

And that’s five. A bit malformed, but what’s floating around in my head for now. When I’m quiet, it’s usually because I’m busy.

-

"The characteristic grid-like simplicity of the view, the absence of barriers… a landscape where nothing officially exists, absolutely anything becomes thinkable, and may consequently happen… — that’s Reyner Banham describing deserts, though I like to imagine he was looking at a spreadsheet." Rod's component of By Hand & By Brain is just wonderful.

-

"Having to learn how to make something ‘the long way’ helps you to understand how to manipulate materials at a fundamental level. It means that you can become fluent. The ability to articulate your thoughts through and with matter, rather than just make it into a shape you have thought of, means that you are more likely to find innovative or creative ways to exploit both materials and machinery. This is true whether you are talking about traditional craft techniques or more contemporary (digital) ways of making: I don’t think you can avoid the notion that time and effort are the only way to get good at something. Using digital technology as a way to shortcut the temporal aspects of craftsmanship is effectively relegating these sources of immense creative potential to the category of ‘labour saving devices’. I am really looking forward to a time where we can fully appreciate the potential for modern digital craftsmanship, by which I mean the skilful manipulation of digital systems as ‘matter’, rather than as express facilitators of shiny objectness." yes-yes-yes-yes.

Automatic switching between viewfinder/LCD screen on Sony RX100m3 not working? Try this.

26 July 2015

I recently had a problem with my Sony RX100 mk3: it wouldn’t automatically swap between displaying in the viewfinder and on the LCD.

If turned on with the viewfinder extended, the viewfinder alone would work; if turned on with the viewfinder shut, the LCD would work. But if the viewfinder was on, raising and lowering it to my eye wouldn’t swap between the two. I spent a while faffing with this, convinced it was broken, and failing to find anything on the internet to discuss this.

Anyhow, then I found this video which explains the problem, and takes a full two minutes to get to the point. So I’m re-iterating that point, in writing, for everybody using a search engine!

Long story short: if you’d guessed that the sensor that detects when it to your eye is playing up, possibly, because of dirt, you’re entirely right. What you might not have worked out is where that sensor is.

It’s here:

It’s not in the viewfinder; it’s to the right of it, on the lip above the LCD. Mine didn’t look dirty, but I wiped it down a few times and sure enough, everything worked fine again. Problem solved, and one of the most useful features of this little camera worked properly again.

-

An even tinier fantasy console – like a Gameboy colour, but coming with an IDE and scripting language, built around Lua. Really nice conceit.

-

A "fantasy console" – a console AND ide/language/design environment inside it for making voxelly games.

-

Lovely graphic design in the animations!

“…this feels like a design problem – design something that works in a display without you having to be there – and it feels like a challenge design courses should be tackling, particularly the interactive ones.”

In his round up of some design shows he went to, Ben’s “grumpy bit” is spot on. I read it both a nod of recognition, and a twinge of stress-memories.

Having been part of installing a large gallery show, as well as putting on my own digital installation, I can safely say: this bit is really hard, and it is really important. It’s not just about turning it on; it’s about keeping it running. Long-term, if it’s a hassle to start, or restart, or you have to restart it too often… eventually, the attendant responsible for that (if there even is one) will get bored.

I learned this once the hard way. That experience definitely informed some of my later work. That’s what this post – which Matt B reminded me existed this week – is really about: reducing an installation to two steps:

- It should work as soon as it’s turned on.

- If it stops working, it should be fixed by turning it off and on again.

That takes the exhibit from requiring technical know-how to maintain to be being maintainable, and even installable, by any attendant. Fingers crossed it won’t fall over; but if it does, it’s a power-cycle away from coming back online.

(This way of thinking is also why, on one of my installations, there’s one LED to indicate that the power is on, and a second to indicate the code has started executing. It makes it easier to confirm when the thing will start functioning.)

Unfortunately, this is often not as straightforward (or interesting) as the rest of the work; it requires building robustness and resilience into the software and/or installation. But the moment you start having to specify lists of software to start in order, or which USB devices to connect in a particular order (so they always appear to your code at the same positions in an array)… the robustness of your project is just gone. And what it leads to is grumpy sighs from tired people in a gallery about digital installations; grumpy attendants or support staff constantly working out what’s going on with it, or putting the ‘out of order’ sign up again.

What that probably means you might have to investigate: all the weird tools at the edge of your chosen platform, like batch files, Applescript, or upstart. How to turn kiosk-mode on in a web browser from a shortcut. How to run things at startup. How to address USB devices by identifiers rather than indicies. How to turn off screen savers / power saving. Etcetera, etcetera.

It’s a tiring part of the last 5% of a project, but it’s almost always the first thing people will see in a gallery space: is your installation working? It might not be part of the design of the thing you’re exhibiting, but it’s sure part of the design of the exhibit – as much as the promotional postcards, the scrapbooks, the placards. Often at graduate shows, exhibits can feel like they’re designed to have the designer there to explain things – but even on a launch night, that’s almost never the case.

When Ben says “design something that works in a display without you having to be there” – well, that’s the default state for an exhibit. On average, you won’t be there. And so that screen, or interactive, or tablet, isn’t just a nice-to-have; it’s a key part of explaining the exhibit (and it might possibly be the exhibit). So it’s worth the effort keeping it turned on.

-

Lovely article on porting Retro City Rampage to MS-DOS – and making it fit on a single floppy disk; reminds me of endless battles with Extended Memory as an end-user, and a nice callback to programming chops of yore. Also: nice to know it was really possible!

-

A quick useful overview of Logic's compressors – specifically, what they emulate, and how to limit them to those original parameters.

-

"Steve Reich’s Clapping Music is a free game that improves your rhythm by challenging you to play Steve Reich’s ground-breaking work – a piece of music performed entirely by clapping. Tap in time with the constantly shifting pattern, and progress through all of the variations. If you slip up or your accuracy falls too low, it’s game over." Must try this.

-

The ruins of the Peckhamplex, as a remarkable diorama, added to and developed over time, from the looks of it. Really uncanny.